Frequently Asked Questions

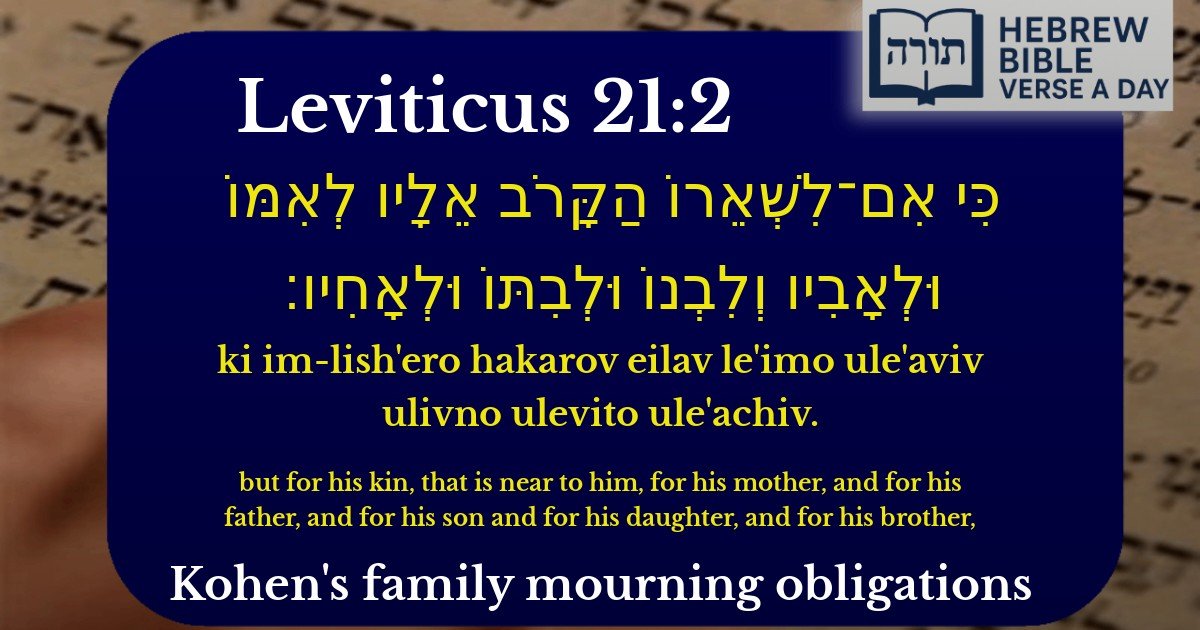

Q: What does Leviticus 21:2 mean?

A: Leviticus 21:2 specifies which close relatives a Kohen (priest) is permitted to become ritually impure for by attending their funeral. According to Orthodox Jewish interpretation, this verse teaches that a Kohen may only become impure for his immediate family members: mother, father, son, daughter, and brother. This is derived from the Torah's words 'for his kin that is near to him.' Rashi explains that this excludes other relatives like a sister who is married (as she is no longer 'near to him' in the same way).

Q: Why is this verse important for Kohanim (priests)?

A: This verse is important because it establishes the boundaries of when a Kohen, who is normally forbidden from contracting ritual impurity (tum'ah), may do so to fulfill the mitzvah of honoring the dead. The Rambam (Hilchot Avel 2:7) rules that a Kohen must become impure for these close relatives, as it is a Torah obligation. This shows the balance between the Kohen's special sanctity and his family responsibilities.

Q: Why isn't a wife mentioned in Leviticus 21:2?

A: The Talmud (Yevamot 22b) discusses this question and concludes that a wife is not explicitly mentioned because the verse refers to blood relatives ('she'er basar'). However, halachically, a Kohen must also become impure for his wife. The Rambam (Hilchot Avel 2:7) explains this is derived from the verse's inclusive language 'his kin that is near to him,' which our sages interpret to include a wife, as she is certainly 'near' to him in the closest sense.

Q: How does this law apply to Kohanim today?

A: Even today, when the Temple is not standing, Orthodox Jewish law maintains that Kohanim must still observe these restrictions. A Kohen may not come into contact with the dead or enter cemeteries except for the immediate relatives listed in this verse. The Shulchan Aruch (Yoreh De'ah 373) codifies these laws, and contemporary poskim (halachic decisors) apply them strictly, though with certain practical considerations for modern circumstances like hospitals.

Q: What lesson can we learn from Leviticus 21:2?

A: This verse teaches us about the Torah's careful balance between different values. While the Kohen has a special level of holiness to maintain, the Torah emphasizes that family obligations take precedence in these cases. The Meshech Chochmah notes that the order of relatives mentioned (parents before children) shows the importance of honoring parents, even for someone as holy as a Kohen. It demonstrates that proper family relationships are fundamental to Jewish life.

Context of the Verse

The verse (Leviticus 21:2) appears in the context of the laws pertaining to Kohanim (priests), specifically addressing the circumstances under which a Kohen may become ritually impure (tamei) by coming into contact with a dead body. While Kohanim are generally forbidden from contracting such impurity, this verse outlines the exceptions—close relatives for whom a Kohen is permitted (and in some cases, obligated) to become impure.

Explanation of the Relatives Listed

The Torah enumerates six categories of relatives for whom a Kohen may become impure:

Halachic Implications

According to the Rambam (Hilchos Avel 2:7), a Kohen is obligated to become impure for these relatives, not merely permitted. This obligation is derived from the phrase "לִשְׁאֵרוֹ הַקָּרֹב אֵלָיו" ("for his kin that is near to him"), which implies a mitzvah to attend to their burial needs.

Exclusions and Additional Insights

The Talmud (Yevamot 22b) notes that certain relatives are not included in this list, such as a married daughter, a sister (unless she is unmarried), or a wife. The exclusion of a wife is particularly noteworthy and is discussed extensively in the Talmud, with the conclusion that a Kohen may not become impure for his wife, though some later authorities (such as the Shulchan Aruch) permit it under certain circumstances.

Moral and Ethical Lessons

The Midrash (Sifra) emphasizes that this mitzvah teaches the importance of family bonds and the dignity of the dead. Even a Kohen, who must maintain a high level of ritual purity, is commanded to prioritize the honor of his deceased relatives. This underscores the Torah's value of chesed shel emes (true kindness), as burial is an act done purely for the deceased's benefit.