Frequently Asked Questions

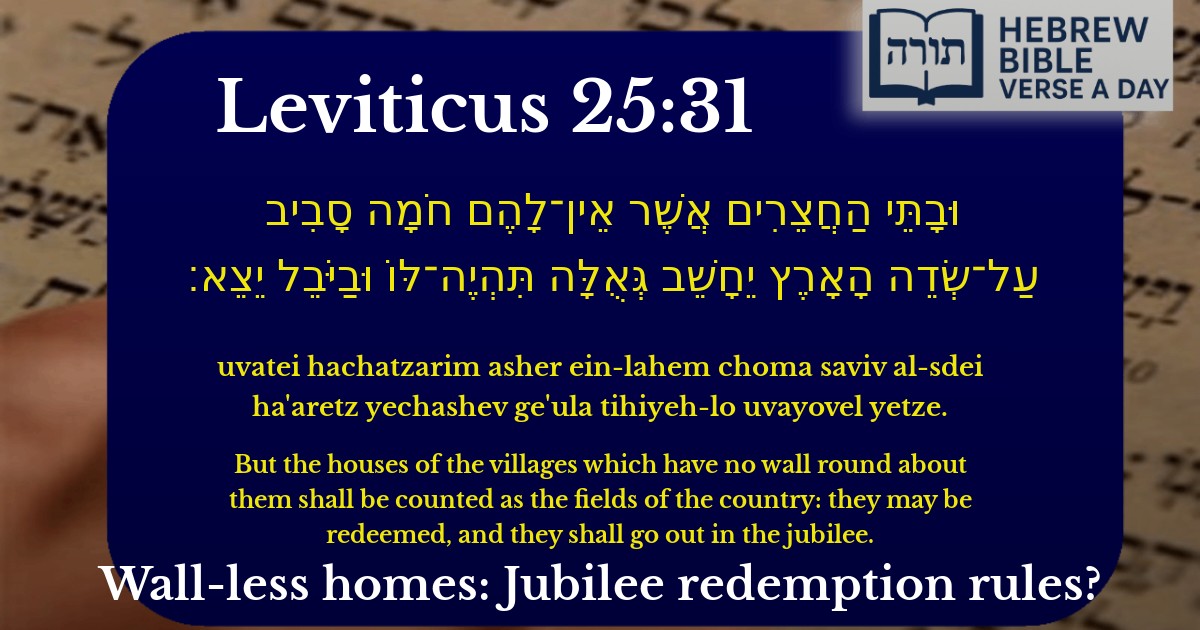

Q: What does Leviticus 25:31 mean?

A: Leviticus 25:31 discusses the laws regarding houses in unwalled villages during the time of the Jubilee year. According to the verse, such houses are treated like open fields—they can be redeemed (bought back) by the original owner, and if not redeemed, they return to the original owner during the Jubilee year. This is in contrast to houses in walled cities, which have different redemption rules (as mentioned in earlier verses). Rashi explains that this distinction emphasizes the permanence of walled cities versus the temporary nature of unwalled villages.

Q: Why is the distinction made between walled and unwalled villages in this verse?

A: The Torah makes this distinction to teach about the different levels of permanence in property ownership. Walled cities represent a more established and secure dwelling, so their houses have stricter redemption laws (as per Leviticus 25:29-30). Unwalled villages, however, are considered more like open land, and thus their houses follow the same redemption laws as fields. The Rambam (Hilchot Shemitta v’Yovel 12:10) elaborates on these laws, showing how they reflect the Torah’s careful balance between ownership rights and social justice.

Q: What practical lesson can we learn from Leviticus 25:31 today?

A: This verse teaches the importance of fairness in property laws and the Torah’s concern for economic justice. Even though the Jubilee laws are not fully applicable today without the Temple, the principle remains relevant: property should not be permanently lost due to temporary hardship. The Talmud (Arachin 33b) discusses how these laws ensure that land ultimately returns to its original owners, preventing generational poverty. Today, this reminds us to support fair and compassionate economic policies.

Q: How does the Jubilee year affect houses in unwalled villages?

A: During the Jubilee year (Yovel), houses in unwalled villages that were sold return to their original owners without payment, just like agricultural land. This is different from houses in walled cities, which only have a one-year window for redemption (Leviticus 25:29-30). The Sforno explains that this law reinforces the idea that unwalled villages are closely tied to the land, emphasizing the temporary nature of such sales and the importance of ancestral inheritance in Jewish tradition.

Q: What is the significance of the term 'redemption' in this verse?

A: In this context, 'redemption' (גְּאֻלָּה) refers to the right of the original owner or a relative to buy back a sold property before the Jubilee year. The Talmud (Kiddushin 21a) discusses the deeper concept of redemption as restoring what was lost, reflecting the Torah’s value of preserving family heritage. The Rambam (Hilchot Shemitta v’Yovel 11:1) outlines the detailed laws of redemption, showing how they protect both the seller and the buyer while maintaining social equity.

Context in Vayikra (Leviticus)

The verse (Vayikra 25:31) discusses the laws of property redemption and the Yovel (Jubilee year), specifically addressing houses in unwalled villages. Unlike walled cities, where houses sold could only be redeemed within one year (Vayikra 25:29-30), unwalled village houses follow the same laws as agricultural land—they may be redeemed at any time and return to their original owners at Yovel.

Rashi's Explanation

Rashi clarifies that unwalled village houses are treated like fields (sdeh ha'aretz) in terms of redemption and Yovel. He emphasizes that the Torah distinguishes between urban and rural properties, with unwalled villages lacking the permanence of walled cities. Thus, their laws align with agricultural land, reflecting their lesser degree of permanence and connection to ancestral inheritance.

Rambam's Legal Perspective

In Hilchot Shemittah V’Yovel (11:7-8), the Rambam codifies this law, stating that houses in unwalled villages follow the same redemption and Yovel rules as fields. This reinforces the principle that land in Eretz Yisrael maintains a sacred, inalienable connection to its original tribal owners, except in walled cities where commerce and urban life necessitate different rules.

Midrashic Insight

The Sifra (Behar 5:4) links this law to the broader theme of divine ownership: "The land is Mine" (Vayikra 25:23). By mandating the return of unwalled properties at Yovel, the Torah underscores that all land ultimately belongs to Hashem, and human ownership is temporary. The distinction between walled and unwalled properties highlights varying degrees of human stewardship.

Practical Implications