Join Our Newsletter To Be Informed When New Videos Are Posted

Join the thousands of fellow Studends who rely on our videos to learn how to read the bible in Hebrew for free!

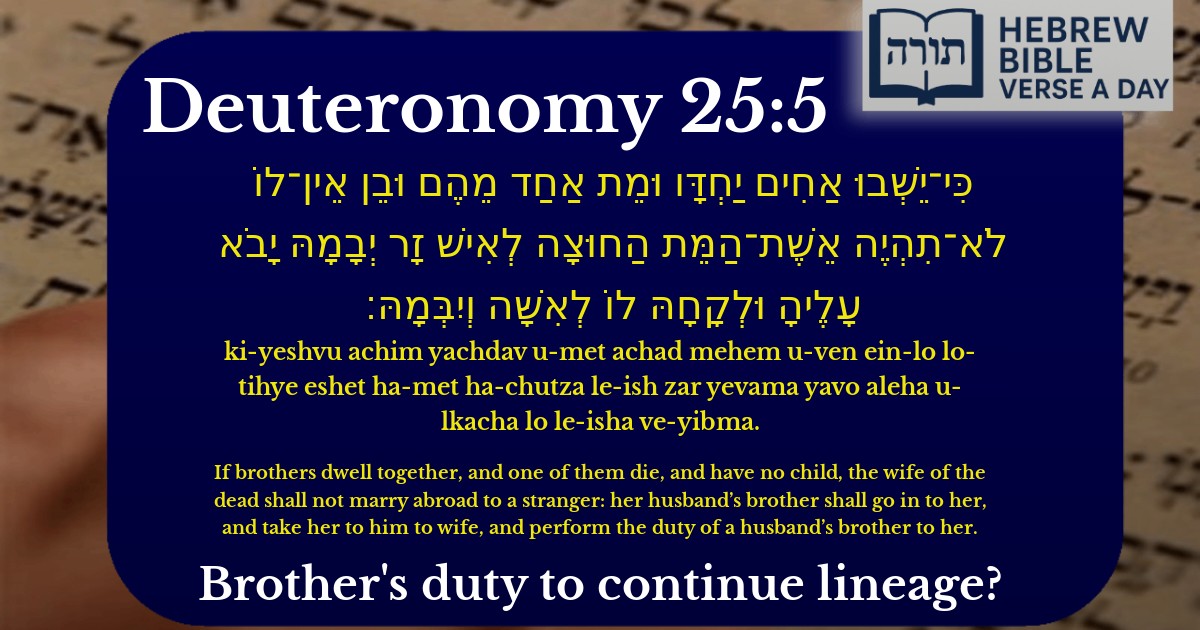

Hebrew Text

כִּי־יֵשְׁבוּ אַחִים יַחְדָּו וּמֵת אַחַד מֵהֶם וּבֵן אֵין־לוֹ לֹא־תִהְיֶה אֵשֶׁת־הַמֵּת הַחוּצָה לְאִישׁ זָר יְבָמָהּ יָבֹא עָלֶיהָ וּלְקָחָהּ לוֹ לְאִשָּׁה וְיִבְּמָהּ׃

English Translation

If brothers dwell together, and one of them die, and have no child, the wife of the dead shall not marry abroad to a stranger: her husband’s brother shall go in to her, and take her to him to wife, and perform the duty of a husband’s brother to her.

Transliteration

Ki-yeshvu achim yachdav u-met achad mehem u-ven ein-lo lo-tihye eshet ha-met ha-chutza le-ish zar yevama yavo aleha u-lkacha lo le-isha ve-yibma.

Hebrew Leining Text

כִּֽי־יֵשְׁב֨וּ אַחִ֜ים יַחְדָּ֗ו וּמֵ֨ת אַחַ֤ד מֵהֶם֙ וּבֵ֣ן אֵֽין־ל֔וֹ לֹֽא־תִהְיֶ֧ה אֵֽשֶׁת־הַמֵּ֛ת הַח֖וּצָה לְאִ֣ישׁ זָ֑ר יְבָמָהּ֙ יָבֹ֣א עָלֶ֔יהָ וּלְקָחָ֥הּ ל֛וֹ לְאִשָּׁ֖ה וְיִבְּמָֽהּ׃

כִּֽי־יֵשְׁב֨וּ אַחִ֜ים יַחְדָּ֗ו וּמֵ֨ת אַחַ֤ד מֵהֶם֙ וּבֵ֣ן אֵֽין־ל֔וֹ לֹֽא־תִהְיֶ֧ה אֵֽשֶׁת־הַמֵּ֛ת הַח֖וּצָה לְאִ֣ישׁ זָ֑ר יְבָמָהּ֙ יָבֹ֣א עָלֶ֔יהָ וּלְקָחָ֥הּ ל֛וֹ לְאִשָּׁ֖ה וְיִבְּמָֽהּ׃

🎵 Listen to leining

Parasha Commentary

📚 Talmud Citations

This verse is quoted in the Talmud.

📖 Yevamot 24a

The verse is discussed in the context of the laws of levirate marriage (yibbum), particularly regarding the obligation of the brother-in-law to marry the widow if the deceased had no children.

📖 Yevamot 39b

The verse is referenced in a discussion about the conditions under which levirate marriage applies, including the requirement that the brothers must have 'dwelt together.'

📖 Kiddushin 7b

The verse is cited in a broader discussion about the legal mechanisms of marriage and the specific case of levirate marriage.

Introduction to Yibum (Levirate Marriage)

The verse (Devarim 25:5) introduces the mitzvah of yibum, the obligation of a surviving brother to marry his deceased brother's childless widow. This practice ensures the perpetuation of the deceased brother's name and lineage in accordance with Torah law.

Rashi's Explanation

Rashi (Devarim 25:5) clarifies the conditions for yibum:

Purpose of Yibum

The Rambam (Hilchos Yibum 1:1) explains that the primary purpose of yibum is to establish the deceased brother's legacy, as the firstborn son from this union will be attributed to the deceased (see also Devarim 25:6). The Midrash (Tanchuma Ki Seitzei 2) further emphasizes that this mitzvah reflects the sanctity of family continuity in Jewish tradition.

Halachic Details from the Talmud

The Talmud (Yevamot 24a) elaborates on the laws of yibum:

Contemporary Practice

In modern times, Ashkenazi practice follows the ruling of Rabbeinu Gershom (c. 1000 CE) prohibiting polygamy, making yibum impossible if the brother is already married. Thus, chalitzah is universally performed (Shulchan Aruch, Even HaEzer 165). Sephardic authorities, while technically permitting yibum in rare cases, generally prefer chalitzah as well (Kitzur Shulchan Aruch 161:1).