Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the meaning of the 'heap' and 'pillar' in Genesis 31:52?

A: In Genesis 31:52, the 'heap' (גַּל, 'gal') and 'pillar' (מַצֵּבָה, 'matzevah') serve as physical witnesses to the covenant between Yaakov (Jacob) and Lavan (Laban). According to Rashi, these markers were set up as a boundary and a reminder of their agreement not to cross into each other's territory with hostile intent. The heap was made of stones, and the pillar was a standing stone, both common in ancient covenants to symbolize the permanence of the agreement.

Q: Why did Yaakov and Lavan make this agreement in Genesis 31:52?

A: Yaakov and Lavan made this agreement to establish peaceful boundaries after years of tension and conflict. Lavan had pursued Yaakov, accusing him of stealing his idols (terafim), but they ultimately decided to part ways peacefully. The heap and pillar served as a tangible reminder of their commitment to avoid future hostilities, as explained in the Midrash (Bereishit Rabbah). This teaches the importance of setting clear boundaries to prevent disputes.

Q: How does Genesis 31:52 apply to resolving conflicts today?

A: Genesis 31:52 teaches the value of creating clear agreements and boundaries to prevent future conflicts. In Jewish tradition, as highlighted by the Rambam (Hilchot De'ot), peaceful resolutions and written or symbolic agreements (like the heap and pillar) help maintain harmony between parties. This verse reminds us to establish mutual respect and avoid actions that could lead to harm, a principle applicable in personal, business, and communal relationships.

Q: What is the significance of using stones as witnesses in Genesis 31:52?

A: Stones were chosen as witnesses because they are durable and long-lasting, symbolizing the permanence of the covenant. The Talmud (Sotah 17a) notes that stones often represent eternity in Jewish tradition. By using a heap and a pillar, Yaakov and Lavan emphasized that their agreement was not temporary but meant to endure, with the stones silently 'testifying' to their promise for generations.

Q: Does Genesis 31:52 have any connection to later Jewish laws or customs?

A: Yes, Genesis 31:52 reflects the Jewish legal principle of 'hagbalah' (setting boundaries), which later influenced halachic (Jewish legal) concepts like 'eruv' (Shabbat boundaries) and property disputes. The Rambam (Mishneh Torah, Laws of Neighbors) discusses the importance of respecting boundaries to avoid harm, echoing the lesson of this verse. The idea of physical markers as witnesses also parallels the use of written contracts (shtarot) in Jewish law to formalize agreements.

Context of the Verse

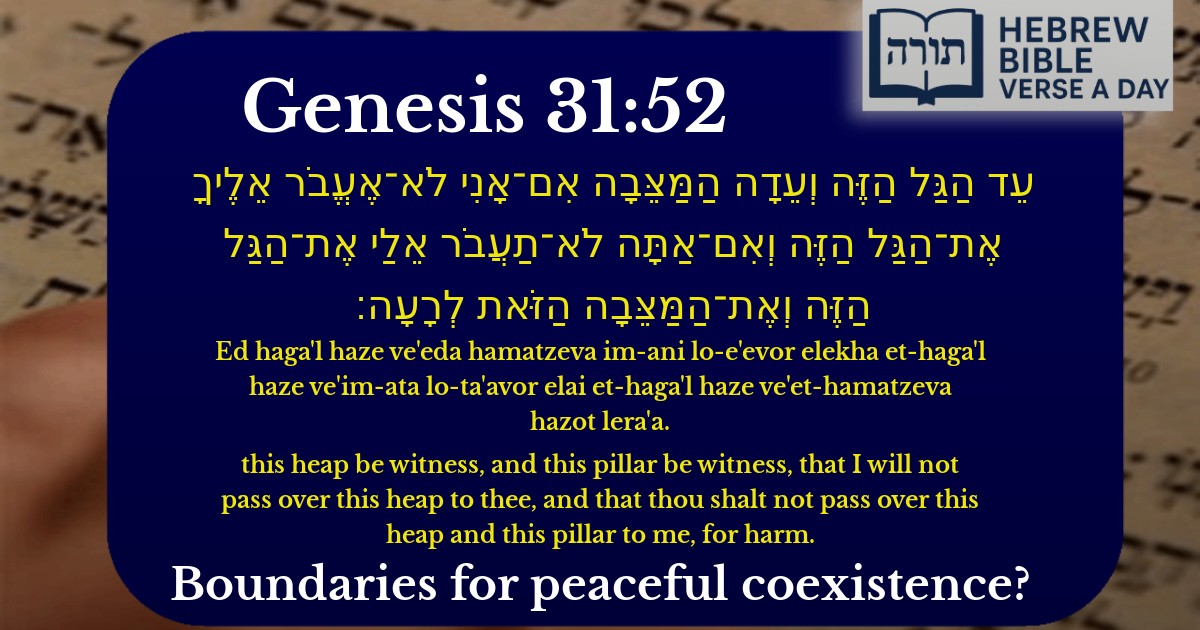

This verse (Bereshit 31:52) is part of the covenant between Yaakov (Jacob) and Lavan (Laban) at Mount Gilad. After years of tension, they establish a boundary marked by a heap of stones (gal) and a pillar (matzevah) as a witness to their agreement not to cross into each other's territory with hostile intent.

Rashi's Explanation

Rashi (Bereshit 31:52) explains that the "gal" (heap) and "matzevah" (pillar) serve as physical witnesses to their treaty. The heap symbolizes the mutual agreement, while the pillar stands as a lasting monument. Rashi emphasizes that these objects were not merely symbolic but carried legal weight in ancient covenants, invoking Divine witness to ensure compliance.

Rambam's Perspective on Covenants

Rambam (Hilchot Melachim 6:1-3) discusses the sanctity of treaties between nations, noting that agreements made with proper intent and witnesses are binding. Though this verse describes a personal covenant, Rambam's principles apply—highlighting the importance of clear boundaries and mutual respect to prevent conflict.

Midrashic Insights

Halachic Implications

The Sefer HaChinuch (Mitzvah 426) connects this verse to the broader Torah principle of keeping oaths and agreements. The heap and pillar serve as a model for how boundaries—physical or moral—must be honored to maintain peace, reflecting the Torah's emphasis on darchei shalom (ways of peace).

Symbolism of the Heap and Pillar

The Kli Yakar (Bereshit 31:52) notes that the "gal" (heap) was a temporary marker, while the "matzevah" (pillar) was permanent. This duality teaches that some agreements may adapt over time (e.g., temporary truces), but core principles (like avoiding harm) remain eternal.