Join Our Newsletter To Be Informed When New Videos Are Posted

Join the thousands of fellow Studends who rely on our videos to learn how to read the bible in Hebrew for free!

Hebrew Text

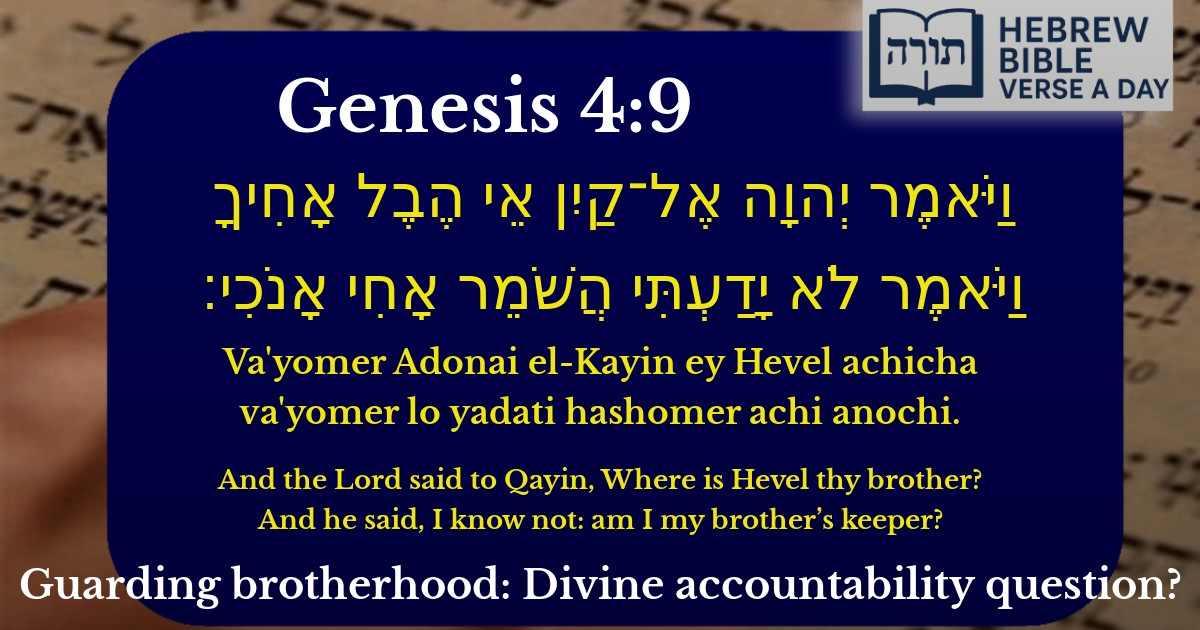

וַיֹּאמֶר יְהוָה אֶל־קַיִן אֵי הֶבֶל אָחִיךָ וַיֹּאמֶר לֹא יָדַעְתִּי הֲשֹׁמֵר אָחִי אָנֹכִי׃

English Translation

And the Lord said to Qayin, Where is Hevel thy brother? And he said, I know not: am I my brother’s keeper?

Transliteration

Va'yomer Adonai el-Kayin ey Hevel achicha va'yomer lo yadati hashomer achi anochi.

Hebrew Leining Text

וַיֹּ֤אמֶר יְהֹוָה֙ אֶל־קַ֔יִן אֵ֖י הֶ֣בֶל אָחִ֑יךָ וַיֹּ֙אמֶר֙ לֹ֣א יָדַ֔עְתִּי הֲשֹׁמֵ֥ר אָחִ֖י אָנֹֽכִי׃

וַיֹּ֤אמֶר יְהֹוָה֙ אֶל־קַ֔יִן אֵ֖י הֶ֣בֶל אָחִ֑יךָ וַיֹּ֙אמֶר֙ לֹ֣א יָדַ֔עְתִּי הֲשֹׁמֵ֥ר אָחִ֖י אָנֹֽכִי׃

🎵 Listen to leining

Parasha Commentary

📚 Talmud Citations

This verse is quoted in the Talmud.

📖 Sanhedrin 37b

The verse is referenced in a discussion about the moral responsibility one has for another's life, emphasizing the importance of not being indifferent to the welfare of others.

📖 Avodah Zarah 22b

The verse is mentioned in the context of discussing the nature of human responsibility and accountability, particularly in relation to the story of Cain and Abel.

Understanding the Dialogue Between Hashem and Kayin

The verse (Bereishit 4:9) records Hashem's question to Kayin, "Where is Hevel your brother?" and Kayin's evasive response, "I do not know; am I my brother’s keeper?" Rashi explains that Hashem, being omniscient, certainly knew where Hevel was. The question was rhetorical—intended to give Kayin an opportunity to confess and repent for his sin of murdering Hevel. Instead, Kayin responds defiantly, denying responsibility for his brother.

Kayin’s Deflection of Responsibility

Kayin’s response, "Am I my brother’s keeper?" reflects his attempt to evade accountability. The Midrash (Bereishit Rabbah 22:9) elaborates that Kayin’s words reveal his hardened heart—he not only denies knowledge of Hevel’s fate but also rejects the moral obligation to care for his brother. The Ramban (Nachmanides) adds that Kayin’s phrasing implies arrogance, as if questioning the very concept of responsibility for another’s well-being.

The Moral Lesson of Brotherhood

The Sforno emphasizes that this exchange teaches a fundamental ethical principle: every person bears responsibility for others. Kayin’s rhetorical question, "Am I my brother’s keeper?" is answered implicitly by the Torah—yes, one is responsible for their fellow. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 37b) derives from this episode the concept of areivut (mutual responsibility), teaching that all Jews are interconnected.

Hashem’s Mercy in Judgment

Despite Kayin’s sin, Hashem engages him in dialogue rather than immediate punishment. The Malbim notes that this demonstrates divine mercy—even when confronting a murderer, Hashem provides an opportunity for introspection and repentance. However, Kayin’s refusal to acknowledge his wrongdoing leads to his eventual punishment (Bereishit 4:11-12).

Key Takeaways from the Verse