Frequently Asked Questions

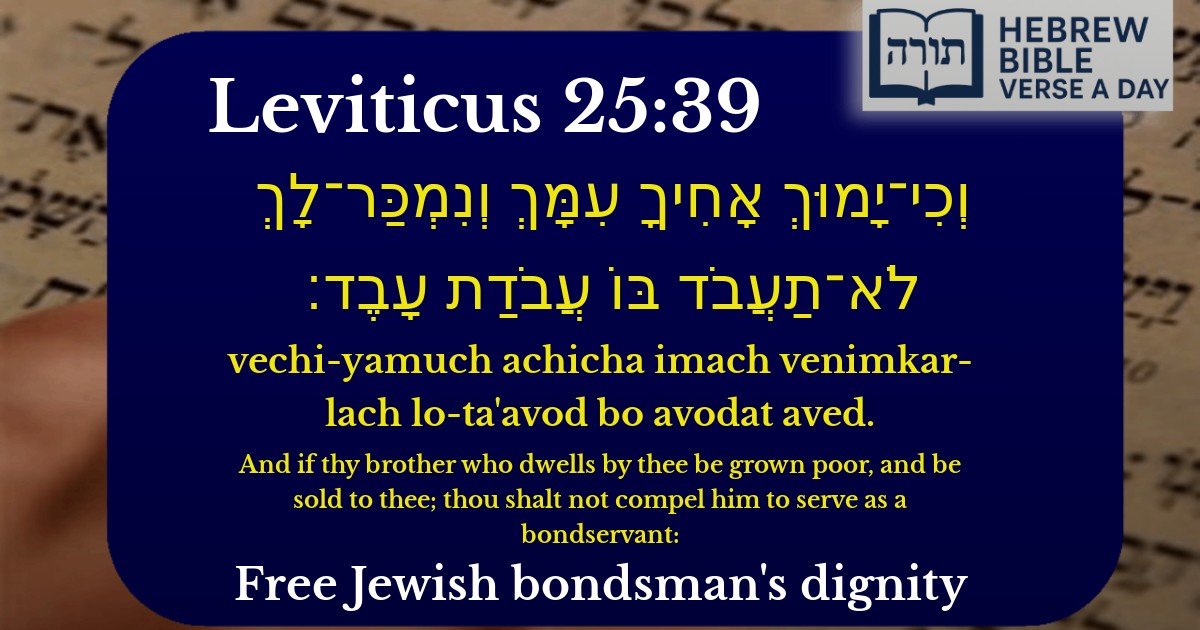

Q: What does Leviticus 25:39 mean when it says 'thou shalt not compel him to serve as a bondservant'?

A: Leviticus 25:39 teaches that if a fellow Jew becomes poor and is sold to you (often to pay off a debt), you must treat him with dignity and not force him into harsh or degrading labor like a slave. Rashi explains that this means assigning appropriate work—not humiliating tasks like carrying your clothes to the bathhouse. The Torah emphasizes compassion even in difficult financial situations.

Q: Why is it important that the verse specifies 'your brother' in Leviticus 25:39?

A: The term 'your brother' highlights that all Jews are part of one family. The Rambam (Hilchos Avadim 1:9) explains that this creates an obligation to treat a Jewish servant with extra care and respect—more like an employee than a slave. This reflects the Torah's value of preserving human dignity, especially for those in vulnerable positions.

Q: How does Leviticus 25:39 apply to employer-employee relationships today?

A: While Jewish servitude does not exist today, this verse teaches timeless principles about ethical treatment of workers. The Talmud (Kiddushin 20a) derives from this that employers must avoid exploitative or demeaning labor conditions. Modern Jewish law applies these ideas to fair wages, respectful treatment, and reasonable work expectations—ensuring workers are valued as human beings.

Q: What's the difference between an 'eved Ivri' (Jewish servant) and a regular slave based on this verse?

A: Leviticus 25:39 establishes that an 'eved Ivri' (Jewish indentured servant) has special protections. Unlike non-Jewish slaves of ancient times, a Jewish servant could not be given crushing labor (Sifra). The Talmud (Kiddushin 22a) notes they also gained freedom after six years or the Jubilee year. This system was meant as temporary financial relief, not permanent subjugation.

Q: Does Leviticus 25:39 mean Jews can never have servants?

A: No—the Torah permits Jewish servitude in specific cases (like paying a debt), but with strict limitations. The verse doesn't ban the practice entirely but forbids abusive treatment. The Midrash (Toras Kohanim) stresses that the servant must live with dignity 'whether young or old' in the household. Ultimately, the goal was rehabilitation, not permanent servitude.

Context and Source

The verse (Vayikra 25:39) appears in the context of the laws concerning the Jubilee year (Yovel) and the treatment of impoverished Jews who are compelled to sell themselves into servitude. The Torah establishes ethical boundaries for how a Jewish master must treat a fellow Jew who has become his servant due to financial hardship.

Rashi's Explanation

Rashi (Vayikra 25:39) emphasizes that the phrase "לֹא־תַעֲבֹד בּוֹ עֲבֹדַת עָבֶד" ("thou shalt not compel him to serve as a bondservant") means that the master may not assign the servant degrading or excessively harsh labor. The servant must be treated with dignity, akin to a hired worker or a resident, not as a slave. Rashi cites the Sifra (a halachic Midrash) to clarify that this prohibition includes tasks like carrying the master's clothing to the bathhouse or fastening his shoes—tasks that symbolize subjugation.

Rambam's Halachic Perspective

In Hilchos Avadim (1:7), the Rambam codifies this law, stating that a Jewish servant may not be given work that is "בלבד" (merely for the sake of subjugation) or unnecessary labor. The master must treat the servant as an equal, as the verse states, "כי עבדים הם לי" ("for they are My servants" - Vayikra 25:42), meaning they are servants of Hashem, not human masters.

Talmudic and Midrashic Insights

Philosophical and Ethical Implications

The verse underscores the Torah's emphasis on human dignity, even in situations of economic disparity. The Sefer HaChinuch (Mitzvah 347) explains that this law trains us in compassion, reminding the wealthy that their financial advantage does not grant them the right to dominate others. The servant retains his inherent worth as a Jew and must be treated accordingly.